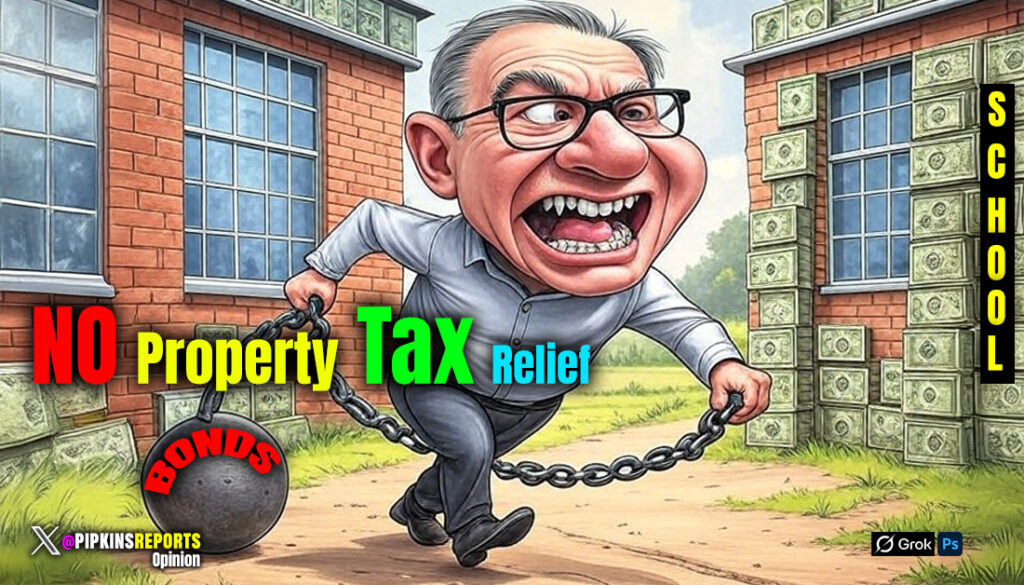

Debt, Not Willpower: How $202.6 Billion in Voter-Approved School Bonds Is the Ball-and-Chain on Eliminating Property Taxes

Austin, TX — The biggest obstacle to lawmakers who promise to abolish or drastically cut school property taxes isn’t partisan gridlock or an unwilling governor. It’s money that voters already agreed to borrow: roughly $202.6 billion in outstanding independent school district bond debt — a sum that, when spread across Texas’ 5.5 million students, works out to about $36,800 per student and effectively locks future legislatures into continuing property-tax collections to pay that debt.

The fairness dilemma: why should the prudent subsidize the spendthrift?

Beyond the staggering numbers, fairness has emerged as a central challenge. When voters in one district approve hundreds of millions in bonds — for new stadiums, performing arts centers, or expansive building programs — those debts become locked-in obligations. But if the Legislature were to eliminate property taxes and shift to a statewide funding model, the costs don’t stay local. Taxpayers in fiscally disciplined districts, who either voted down bonds or avoided extravagant projects, would end up subsidizing the debt of their neighbors.

This creates a thorny equity problem: one community’s appetite for borrowing can effectively hold the entire state hostage, delaying property-tax elimination for everyone. Responsible districts — those that avoided over-leveraging their tax base — are forced into the same long repayment cycle as the districts that went all-in on debt. Lawmakers warn that unless Texas finds a way to firewall these obligations, the drive to abolish school property taxes statewide will continue to falter.

The numbers you need to know

A Texas Policy report and the state’s debt-tracking data show that outstanding ISD bond debt reached $202.6 billion in the most recent reporting year — the largest single component of local government borrowing in Texas.

Spread across Texas’ student enrollment, that comes to roughly $36,800 per student. That debt does not vanish if lawmakers change the tax code. It remains a contractual obligation backed by the taxing authority that issued it — and this legal reality ties the Legislature’s hands.

Lawmakers on record: bonds drive the property-tax problem

“Taxes are higher than if there was no bond … so every bond effectively is a tax increase,” said Rep. Brian Harrison (R-Midlothian) during a 2023 debate about school finance.

Rep. Morgan Meyer (R-Dallas), who carried HB 19 in 2025 to curb runaway local debt, framed it directly: “We can’t talk about eliminating property taxes while leaving the bond spigot wide open. Every dollar borrowed today is a tax locked in for the next 20 to 30 years.”

These blunt statements reflect why the bulk of legislative proposals in recent years have targeted future bond elections — raising voter approval thresholds, moving them to higher-turnout November ballots, and requiring more transparency about long-term costs. None of these measures erase the existing debt, but they aim to prevent further accumulation that would worsen the fairness gap between districts.

The political paradox: voters approved the problem

The irony is that most of this debt wasn’t foisted on Texans by bureaucrats alone — voters themselves approved these bonds at the ballot box. In many cases, school districts have resorted to scare tactics and emotional appeals to secure that approval.

The pitch is often less about fiscal prudence and more about guilt. Campaign slogans and superintendent talking points regularly frame the choice in moral terms: “If you don’t approve this, you must not support teachers,” or “Our teachers deserve more,” or the ever-present line, “It’s for the children.” Newer tactics now include, “You must not have children in school.” , “Teachers are paying out of their own pockets.” These carefully crafted appeals make resistance politically difficult, especially in tight-knit communities where opposing a bond can be painted as opposing kids or education itself.

And the strategy has worked. Across Texas, billions in bonds have sailed through under this messaging, saddling districts with long-term debt and tying the hands of future legislatures. The political paradox is this: the same voters who demand relief from crushing property taxes are also the ones who — swayed by emotional campaigns — have made that relief harder to achieve by approving bonds that lock in tax obligations for decades.

But those local “yes” votes have statewide consequences. The debt must be repaid, and repayment requires continued property-tax collections. For legislators aiming to abolish school property taxes, the very taxpayers clamoring for relief are also the ones who made that task exponentially harder by approving bonds.

Options — none are painless

- State buyout of local debt: A one-time appropriation of $202.6 billion is politically and fiscally unrealistic.

- Refinancing or defeasing debt: Lowers payments but doesn’t erase obligations.

- Raising voter thresholds for new bonds: Limits future growth but doesn’t fix existing debt.

- State assumption of debt: Shifts the burden, raising fairness concerns between high-debt and low-debt districts.

Each option forces the same uncomfortable conversation: who pays for decisions already made?

Bottom line

The dream of eliminating school property taxes runs headfirst into a wall of accumulated debt — $202.6 billion worth of it, or $36,800 per student. And until Texans reconcile the fairness problem — why should one district’s fiscal responsibility be undercut by another’s binge borrowing? — the debate will remain stuck.

Worse still, there’s a sleight of hand at work in many school districts. As soon as one bond issue approaches its final payment, local boards are quick to put another bond on the ballot. Instead of allowing taxpayers to enjoy the natural drop in property-tax rates that should come with retired debt, they simply roll that expiring tax into a new long-term obligation.

Districts then market these bonds with the line, “This will not raise your tax rate.” Technically true — but deeply misleading. What they are really saying is that your tax rate will not go down as it should have. The tax reduction that rightfully belongs to homeowners is effectively stolen, replaced with a new debt service that locks in the same tax burden for decades more.

This cycle ensures that property taxes never truly fall, even when debt is paid off. It’s a fiscal treadmill: as old obligations expire, new ones are issued, keeping taxpayers perpetually on the hook. That practice is one reason why the total statewide school bond debt has continued to climb rather than shrink.

For lawmakers and taxpayers alike, the conclusion is unavoidable: unless the bond game itself is reined in, every promise of property-tax elimination will remain an illusion. Texans cannot escape the burden of perpetual debt service so long as school districts treat bond expirations not as a chance to lower taxes, but as an opportunity to keep the gravy train running.